Trusted by design (part 1): define your software’s mission and scope#

No project exists in a vacuum. Open-source software is a vast web of inter-connected and inter-dependent tools. When creating a new tool, your number one job is to carve out its place in the web consciously, openly and from the outset. How can you approach that?

Note

This is the first of three blogposts on the theme of Trusted by design: set up your research software for community adoption. See the introductory blogpost for context.

The task is no different to scoping out research projects, which also live within a vast web—the scientific literature. You hang out in a research field that looks inviting and stumble upon a gap, or a discrepancy that won’t go away. You work to rectify it until, eventually, you discover a new piece of knowledge. You are not done—you must stitch that new piece back into the web of ideas. You do that by clearly articulating the gap filled by your piece and how the web is rearranged by it.

Pinpointing your position on the web may be necessary at the end, but it’s useful from the very beginning. You may have heard lots of advice on doing that effectively in a research context. The practice I like most is writing down your project’s abstract before you even start. You imagine your research completed and write the abstract of your envisioned manuscript as best you can. Of course that abstract will change as you go along. But that’s the point. The abstract is not your destination. It’s your compass—your protection from getting lost in the sea of knowledge.

Software abstracts#

What’s the equivalent of an abstract for a software package? There’s no standardised format for it, but if you browse through the READMEs and websites of your favourite tools you will start seeing some common patterns.

You will often find a single-sentence, high-level description of the project—the mission statement. It sometimes takes the form of a tagline under the project’s title, or it can live in a dedicated page called “About us”, or just “Mission”. Let’s look at some examples for scientific Python packages, including some we develop:

Project |

Mission statement |

|---|---|

pandas aims to be the fundamental high-level building block for doing practical, real world data analysis in Python. |

|

napari aims to be the multi-dimensional image viewer for Python and to provide GUI access to a plugin ecosystem of image analysis tools for scientists to use in their daily work. |

|

The BrainGlobe Initiative exists to facilitate the development of interoperable Python-based tools for computational neuroanatomy. |

|

movement aims to facilitate the study of animal behaviour by providing a suite of Python tools to analyse body movements across space and time. |

The mission statement is often supplemented by more information, such as:

The project’s aims, akin to what you’d find in a scientific grant; see BrainGlobe’s homepage for an example.

The project’s values and design principles; napari does that well.

The project’s scope, i.e. the set of tasks it is designed to enable; see pandas’ “Library Highlights” section.

Case study: movement#

When I started developing movement, my colleagues and I consciously chose to write a ‘software abstract’ before we began the work. We did that by first mapping out our neighbourhood—open-source tools for analysing animal behaviour. This meant doing lots of research upfront: googling, reading papers, browsing GitHub, and also talking to many researchers working in this field. We tried to condense our findings into a set of common workflows and broke them down into tasks. We zeroed in on tasks that were arduous and under-served by existing tools—the potential gaps to address.

Next, we asked whether these gaps merited being addressed by a standalone package or by contributing to existing projects. We also asked ourselves if we were the right people to address each gap.

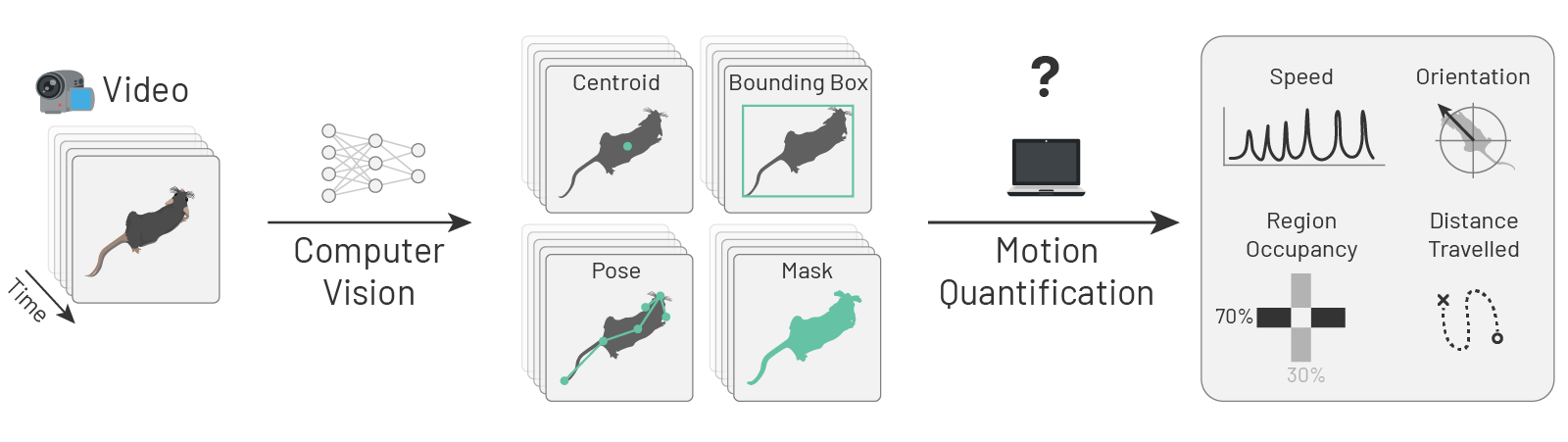

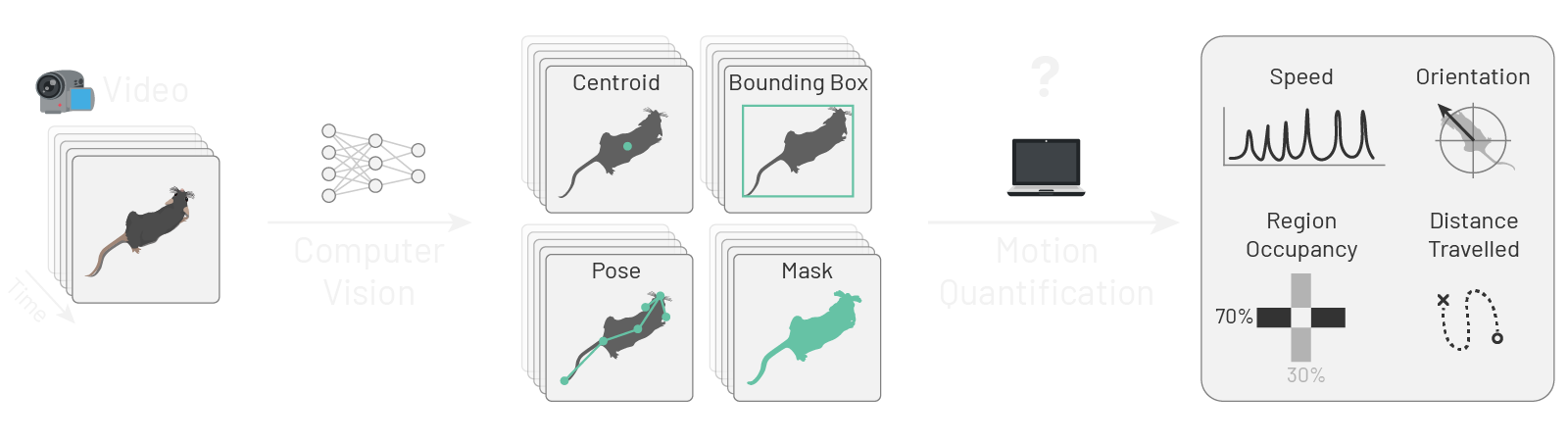

Through this process we concluded that the deep learning revolution of the last decade had already trickled down into user-friendly open-source packages. Tools such as DeepLabCut and SLEAP enabled researchers to track animal movements in videos accurately, cheaply, and at scale. This welcome development had moved the analysis bottleneck downstream of motion tracking: turning this swell of data into quantitative descriptions of behaviour. Researchers would often use the same behavioural metrics across projects and disciplines. But these were typically implemented as fragile, in-house scripts that were seldom maintained beyond a project’s conclusion. We saw an opportunity for a general-purpose Python toolbox that would ingest motion tracking data from existing frameworks and provide validated and documented implementations for various common behavioural metrics.

A schematic illustration of the gap in the open-source ecosystem for animal behaviour analysis that movement aims to fill.#

A schematic illustration of the gap in the open-source ecosystem for animal behaviour analysis that movement aims to fill.#

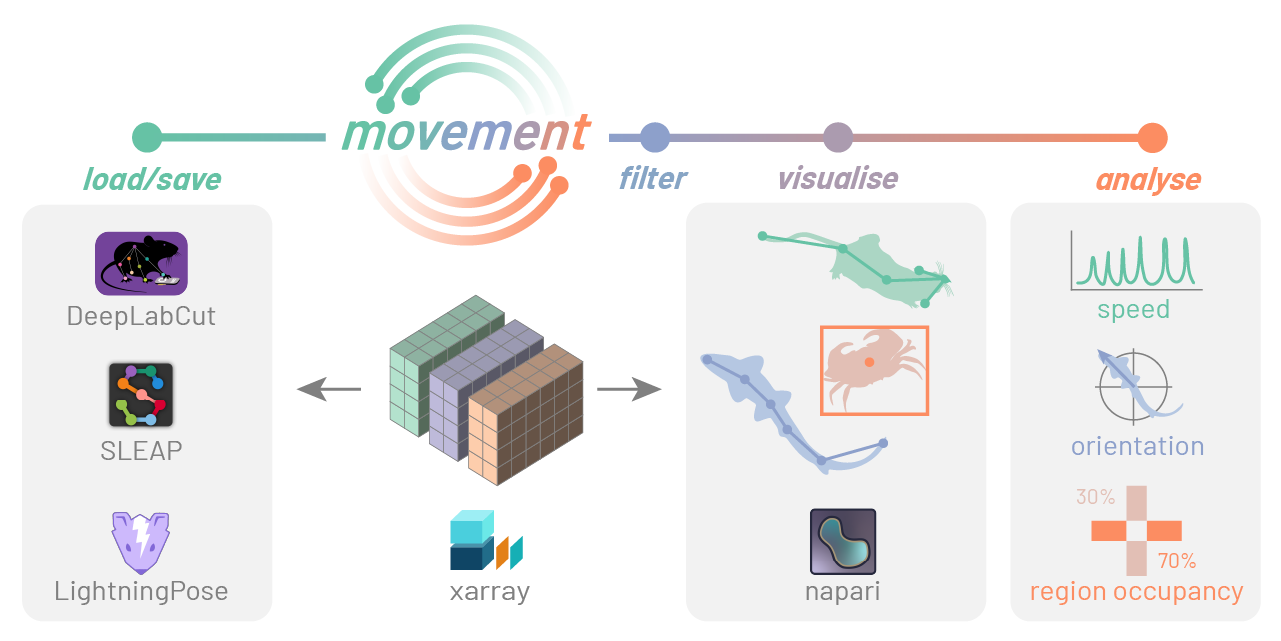

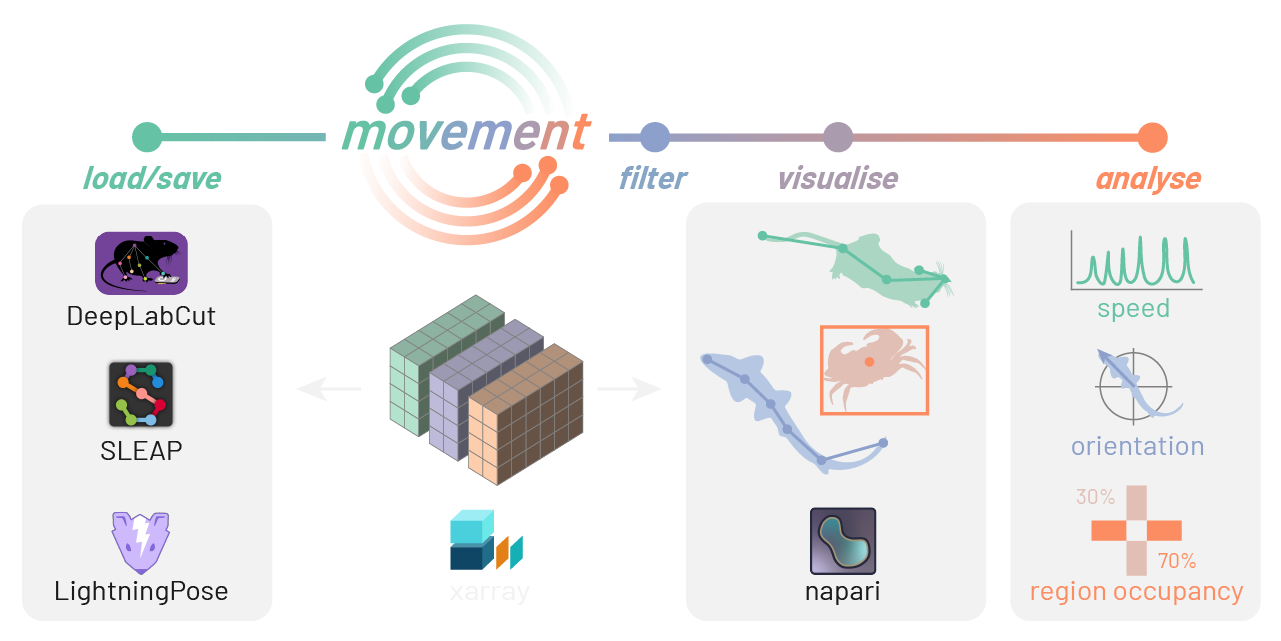

And that’s how movement’s ‘abstract’ was born. You just read it. You can find a version of it on the project’s homepage. Over time we expanded that into a whole page detailing the project’s mission, scope, and design principles.

You may have noticed that the homepage also contains a visual overview of the project—a graphical abstract of sorts. I love a good visual, so I felt a natural urge to literally sketch things out. This graphical abstract has evolved over time and we’ve found it useful in communicating the project’s mission and scope at a glance. It’s faster to parse—and more memorable—than a wall of text.

A graphical abstract for the movement project, including the key tasks it covers and how it relates to other tools.#

A graphical abstract for the movement project, including the key tasks it covers and how it relates to other tools.#

The many benefits of an abstract#

No-one would argue against defining your work’s aims. What I want to emphasise are the benefits of doing so in the open and at the very beginning, before you write a single line of code.

How does this help with community adoption? Let’s look at some scenarios inspired by real events.

While writing the abstract:

You discover that existing tools already cover your project’s scope. No need to reinvent the wheel—you save time, other projects grow stronger.

The deeper you dig, the more you see a pressing need. Articulating it in writing gives you clarity of purpose and lets you plan the work in reasonable chunks. You’re ready to advocate to colleagues, managers, and funders. You may recruit collaborators and secure resources.

During the project’s early days:

People grasp your project’s essence at a glance and decide whether to engage. You attract the right attention and gain early adopters.

Someone reaches out and points you to their cool project. It seems quite similar to yours, but you’d missed it in your initial research; it happens. You decide to have a chat, which may lead to one of several outcomes:

Their project is further along with many users. You decide to stop working on your project and contribute to theirs instead. Your visions merge into something bigger and better.

Despite appearances, there isn’t much overlap. There’s room for both tools. You update your abstract to clarify how they differ.

There is overlap, but you disagree with their approach, or the two projects are hard to reconcile from a technical standpoint (e.g. use different programming languages). You keep developing your software—every ecosystem benefits from diversity. Perhaps it’s time to articulate your design principles and your technical choices.

A real-world example

In the early days of movement, Mikkel Roald-Arbøl reached out to us because he was developing

anibehavr, an R package with a similar scope. Mikkel has since become one of our most valued collaborators. We decided to keep both projects going—one for Python, one for R. We are also working together to gradually converge on common data standards and workflows. Mikkel has since renamed his project to animovement to better reflect its complementarity to movement.

Throughout the project’s lifecycle:

Someone raises a GitHub issue requesting a feature. Your written scope guides you:

In scope: it goes on the to-do list. You ask if they’d help implement or test. You just made a friend.

Out of scope: you close the issue with a clear explanation.

Borderline: you update your scope so the feature falls clearly in or out. Editing is easier than writing from scratch—this is how real scopes evolve.

You and a collaborator disagree on how to build a feature: you want to delegate the work to an existing library (adding a dependency in the process) while they want to implement the functionality from scratch. You consult your design principles and find one prioritising easy cross-platform installation. The library you proposed doesn’t support all platforms—so you concede. The disagreement resolves on merits.

Now imagine these scenarios without a public abstract. Misunderstandings are more likely to arise. Decisions that felt principled to you may look arbitrary to others—and that erodes trust.

The takeaway#

Your software abstract is more than a planning document—it’s a trust signal. By articulating your mission publicly before the stakes are high, you invite collaboration and scrutiny early. You show that you’re building something thoughtfully, not just hacking code together. And when disagreements arise—as they will—you have something to point to. Not the final word, but a starting point for conversation.

In the next post, we’ll explore how to turn your abstract into action while maintaining trust—by releasing early and often.