Introduction to Python

Schedule

- Aims

- Why learn Python?

- Basics

- Variables

- Data types

- Loops

- Conditional statements

- List comprehensions

- How to work with Python? (using IDEs, environments, etc…)

- Writing your first Python script

- Loading and saving data

Schedule

- Recap and Q&A

- Functions and methods

- Classes and objects

- Errors and exceptions

- Integrated Development Environments (IDEs)

- Virtual environments

- Modules and packages

- Organising your code

- Documenting your code

Aims

- Introduce Python

- Introduce some basic programming concepts

- Show you one (our) way of doing things

- Not necessarily the best or only way

- Give you the confidence to start doing it yourself

- Prepare you for other courses

Please ask any questions at any time!

Installation

Install miniforge

Click here to go to the download page

Add Miniforge to PATH when prompted during installation.

Try the below in either your terminal (Mac/Linux) or Miniconda Prompt (Windows):

Windows troubleshooting

- Did you had a previous version of Anaconda installed? You might need to uninstall it first.

conda not found? Runconda initin your terminal.

Install an IDE

- Visual Studio Code - customisable, extensible, open source

- PyCharm - opinionated defaults, not fully free (free for educational use)

Install a text editor (macOS)

- Sublime Text - lightweight text editor

- Windows can use the built-in Notepad or Notepad++

Install git

- Install Git - version control system

Why learn Python?

Why learn Python?

Popularity

- Python is the most popular programming language for data science\(^1\)

Free and open source

- Unlike MATLAB, IGOR, etc…

- Anyone can use your code

- 9.7M open Python repositories\(^2\) on

- 9.7M open Python repositories\(^2\) on

Versatile Not just for data analysis / machine learning

- Visualisation

- Web development

- Data acquisition

Why learn Python?

Packages for everything!

Numpy: arrays

Pandas: dataframes

SciPy: scientific computing

SciPy: scientific computing

Scikit-image: image analysis

Scikit-image: image analysis

PyTorch: machine learning

Matplotlib: plotting

People have spent lots of time optimising these packages! Don’t reinvent the wheel!

Interactive Python

Terminal

- A text based interface to interact with your operating system

- You can run programs, manage files and folders, install software, etc.

- Many names:

- Command Prompt

- PowerShell

- Terminal

- Shell

- Git Bash

- Anaconda/minforge Prompt

Terminal

- Typically arguments are separated by spaces

- Named arguments are preceded by

--or-(double or single dash) - Help is usually available with

-h,--helporman <command> - Cancel a running command with

Ctrl+CorCtrl+Z Tabkey to autocomplete commands and file namesUpandDownkeys to cycle through command historyq(typically) to quit multi-page outputspythonis a program that can be run from the terminal

Ways of working with Python

REPL(Read-Eval-Print Loop), “interactive Python”, “Python console”Jupyter notebooks(.ipynb)Scripts(.py)

Using interactive Python (REPL)

Demo time! 🧑🏻💻👩🏻💻

Basics of Python

Variables

- A variable is a name that refers to a value

- You can use variables to store data in memory

- You can change the data stored in a variable at any time

- Allows you to reuse data without having to retype it

Variables

The value of a is:

1The value of c is:

3Variables

The value of a is now:

2The value of x is:

10

The value of y is:

20Data types

- Different kinds of data are stored in different ways in memory

- You can use the

type()function to find out what type of data a variable contains

Strings

- A string is a sequence of characters

- Strings are enclosed in single or double quotes

- Used to represent text

Strings

<class 'str'>

I want to learn Python!- Algebraic operations can have different meanings for different data types

- Try

a*3in the code above

- Try

f-strings

- f-strings are a way to format strings

- Use

fbefore the string - Use

{variable}to insert variables into the string

f-strings

You can also use f-strings to format numbers

Question

- What is the type of…?

100'Dog'3.14printFalse'50'None

Question

- Can you add an int and a float?

Lists

- Ordered collection of values

- Enclosed in square brackets

[] - Any data type, including mixed types

- Indexed from 0 with square brackets

[] - Mutable (can be changed)

Question

- Find the third element from

my_list?

- Change the second element to

3.0?

- What happens if you request

my_list[5]?

Tuples

- Ordered collection of values

- Enclosed in parentheses

() - Any data type, including mixed types

- Immutable (cannot be changed)

- When would you use a tuple instead of a list?

Unpacking

Question

- How would you turn

my_listinto a tuple?

- How would you turn

my_tupleinto a list?

Dictionaries

- Collection of key-value pairs

- Enclosed in curly braces

{} - Keys are unique and immutable

dict_keys(['a_number', 'number_list', 'a_string', 5.0])

dict_values([1, [1, 2, 3], 'string', 'a float key'])

dict_items([('a_number', 1), ('number_list', [1, 2, 3]), ('a_string', 'string'), (5.0, 'a float key')])

string

a float keyQuestion

Conditional statements

Question

- Write a loop that goes through the numbers 0 to 10

- For each number, print whether it is even or odd

- Hint: use the modulus operator

%and==to check for evenness

- Hint: use the modulus operator

Using and and or

For loops

For loops

- You can loop over any iterable

- Use

_if you don’t need the loop variable enumerate()gives you the index and the valuerange()generates a sequence of numbersrange(n)from 0 to n-1range(a, b)from a to b-1range(a, b, step)from a to b-1 with jumps of step

My pet is a: cat

My pet is a: dog

My pet is a: rabbitBreak and continue statements

Question

- Create a list of integers from 0 to 5

- Use a loop to find the sum of the squares of the integers in the list

- Print the result

55While loops

- What if you don’t know when you should stop iterating?

- Use

while! - Does something while a condition is met

Not there yet...

Result is 0

Not there yet...

Result is 1

Not there yet...

Result is 2

Not there yet...

Result is 3

Not there yet...

Result is 4

Not there yet...

Result is 5

Not there yet...

Result is 6

Not there yet...

Result is 7

Not there yet...

Result is 8

Not there yet...

Result is 9

We got there!Question

- Write a loop that only prints numbers divisible by 3 until you get to 30

- But skip printing if the number is divisible by 5

- Use a while loop

List comprehensions

- Concise way to create lists

[expression for item in iterable]

- Can include conditions

[expression for item in iterable if condition]

Question

- Create a list of square even numbers from 1 to 10 using a list comprehension

Writing your first Python script

Ways of working with Python

REPL(Read-Eval-Print Loop), “interactive Python”, “Python console”Jupyter notebooks(.ipynb)Scripts(.py)

Writing your first Python script

Demo time! 🧑🏻💻👩🏻💻

Loading and saving data

Writing files

- Python can open files in various modes:

- ‘r’ - read (default)

- ‘w’ - write (create or overwrite)

- ‘a’ - append (adds to the end of the file)

- Always close the file after you’re done

- Use

withto do this automatically

Reading files

Demo

- Let’s write a script that saves the below data to a comma-separated file

Demo

Functions

Functions

Functions

- Time consuming and error prone to repeat code

- Functions allow you to:

- Reuse code

- Break problems into smaller pieces

- Scope defined by indentation

- Defined using the

defkeyword - Can take inputs (arguments) and return outputs

Exercise

- Write a function to check that a password is at least 8 characters long

- The function should take a string as input and return

Trueif the password is long enough, andFalseotherwise - You can use the built-in

len()function to get the length of a string

Exercise

True

FalseArguments

- Functions can take multiple arguments

- Positional arguments

- Must be given in the correct order

- Keyword arguments

- Can be given in any order

- Use the syntax

name=value - Must come after positional arguments

- Default arguments

- Have a default value if not provided

- Must come after non-default arguments

Arguments

First animal: dog

Second animal: cat

Third animal: penguinFirst animal: cow

Second animal: elephant

Third animal: penguinArguments

Cell In[63], line 1 def list_animals(first="dog", second, third="penguin"): ^ SyntaxError: parameter without a default follows parameter with a default

Exercise

- Write a function that takes two strings as arguments and prints the longer of the two strings

- One of the arguments should have a default value of an empty string

Exercise

banana

appleUsing * and **

*and**are upacking operators, useful to unpack tuples, lists and dictionaries- You might have seen the syntax

*argsand**kwargsbefore - This is just a convention to indicate that the function takes a variable number of arguments

Unpacking positional arguments: (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Unpacking keyword arguments: {}

Unpacking positional arguments: ()

Unpacking keyword arguments: {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3}Using * and **

Unpacking positional arguments: (1, 'a', 3.14)

Unpacking keyword arguments: {}

Unpacking positional arguments: ()

Unpacking keyword arguments: {'name': 'John', 'age': 30}

Unpacking positional arguments: (1, 2, 3)

Unpacking keyword arguments: {'name': 'Jane', 'city': 'New York'}How are *args and **kwargs useful?

*argsand**kwargsare useful when you don’t know which arguments will be passed to the function- Or when you wrap another function and want to pass all arguments to the wrapped function

Return values

- Functions can return one or more values

- Use the

returnkeyword - A function can have multiple return statements but only one will be executed

- If no return statement is given, the function returns

None

Return values

Classes and objects

Objects

- Everything in Python is an object

- Integer, float, string, list, functions…

- Objects have attributes and methods

- Attributes: properties of the object

- Methods: functions that belong to the object

Classes

- A class is a blueprint for creating objects

- Defined using the

classkeyword - Can have attributes and methods (functions)

__init__method is called when an object is createdselfrefers to the instance of the class

Exercise

- Try adding a new attribute

noiseto theAnimalclass - Add a method

make_noisethat prints the noise of the animal

Exercise

nootErrors and exceptions

Errors and Exceptions

- You’ve probably seen an error already

- If not try these, why don’t they work?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ModuleNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[81], line 1 ----> 1 import london ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'london'

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[82], line 1 ----> 1 len(print) TypeError: object of type 'builtin_function_or_method' has no len()

SyntaxError

- Something is wrong with the structure of your code, code cannot run

- What’s wrong below?

Cell In[84], line 1 print hello ^ SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'. Did you mean print(...)?

Exceptions

- Something went wrong while your code was running

- What’s wrong in these examples?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[87], line 1 ----> 1 1 / 0 ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- NameError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[88], line 1 ----> 1 giraffe * 10 NameError: name 'giraffe' is not defined

Tracebacks

- Help you find the source of the error

- Read from the bottom up

- Look for the last line that is your code

- Debugging manifesto 🐛

Tracebacks

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[90], line 7 4 def call_func(x): 5 y = divide_0(x) ----> 7 z = call_func(10) Cell In[90], line 5, in call_func(x) 4 def call_func(x): ----> 5 y = divide_0(x) Cell In[90], line 2, in divide_0(x) 1 def divide_0(x): ----> 2 return x / 0 ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Tracebacks

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[91], line 8 5 return none_function() 7 file_name = none_function() ----> 8 open_file = open(file_name) File ~/.local/lib/python3.12/site-packages/IPython/core/interactiveshell.py:343, in _modified_open(file, *args, **kwargs) 336 if file in {0, 1, 2}: 337 raise ValueError( 338 f"IPython won't let you open fd={file} by default " 339 "as it is likely to crash IPython. If you know what you are doing, " 340 "you can use builtins' open." 341 ) --> 343 return io_open(file, *args, **kwargs) TypeError: expected str, bytes or os.PathLike object, not NoneType

Handling exceptions

- What if you know an error might happen?

5.0--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[92], line 5 2 print(x / y) # This might raise an error 4 divide(10, 2) ----> 5 divide(10, 0) Cell In[92], line 2, in divide(x, y) 1 def divide(x, y): ----> 2 print(x / y) ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Handling exceptions

- What if you know an error might happen?

- You can handle it with

tryandexcept

Handling exceptions

- What’s the problem with this code?

- Don’t make your

excepttoo general!

Result: 5.0

Y cannot be zero!

Both x and y must be numbers!Exercise

- Write a function to return the length of the input

- If the object has no length, return

None

Exercise

5

None

3IDEs

IDEs: Integrated Development Environments

- Used by most developers

- Allows you to switch between the three main ways of working with Python

- Within the same program you can:

- Edit → Text editor 📝

- Organise → File explorer 📁

- Run → Console 💻

Example IDEs

- Visual Studio Code - more customizable

- PyCharm - optimized for Python

- …

You can click on the name to go to the download page.

Install the one you like most!

Igor prefers PyCharm, Laura prefers VS Code.

Using IDEs

Using IDEs

Using IDEs

Using IDEs

Using IDEs

Virtual environments

Scientific Python ecosystem

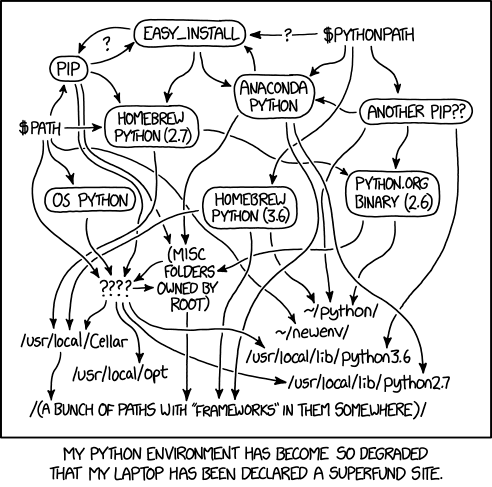

Virtual environments

- Many packages are continuously developed 🔁

- This means there will be breaking changes

- Some packages will require specific versions of other packages

- Similar with Python versions

- New versions of Python may introduce new features or deprecate old ones

Virtual environments

Virtual environments

- Many packages are continuously developed 🔁

- This means there will be breaking changes

- Some packages will require specific versions of other packages

- Similar with Python versions

- New versions of Python may introduce new features or deprecate old ones

- How can we have two versions of the same package installed at the same time?

- Virtual environments! 🎉

Virtual environments

Conda environments

- Conda is a

package managerandvirtual environment manager - Separates Python environments from each other (and from system Python)

- Can also manage non-Python packages (e.g. R, C libraries, etc…)

- Reproducible environments that can be shared with:

- Collaborators

- Readers of your paper

- Future you (HPC, etc…)

Environment management

In your terminal (use Anaconda Prompt on Windows):

- Creates a new environment named

python-intro - Installs Python 3.13 and Jupyter Notebook in that environment

Environment management

In your terminal (use Anaconda Prompt on Windows):

- Remember to activate the environment before using it!

Environment management

In your terminal (use Anaconda Prompt on Windows):

- Deactivates the current environment

Environment management

In your terminal (use Anaconda Prompt on Windows):

- Lists all conda environments on your system

Environment management

In your terminal (use Anaconda Prompt on Windows):

- Deletes the

python-introenvironment and all its packages

Modules and packages

Standard library

- A module is a file containing Python code

- A package is a collection of modules

- The standard library is a set of modules that come with Python

- It provides a wide range of functionality

- File I/O

- Time and date handling

- Math and statistics

- Accessed using the

importandfromkeywords

Installing a third-party package

Important

- In the terminal, not in the Python console!

- Remember to activate the conda environment first

Using packages

Importing packages

- You can import all available functions in a package

- You can import a specific function from a package

- Use

from ... import ...

- Use

- You can also rename the package or function using

as- Common convention for

pandasispd

- Common convention for

Installing packages

Exercise

In your conda environment, using pip:

- Install

numpy - Uninstall

numpy - Install

numpyversion1.26.4 - Update the installation of

numpy - Install

matplotlibandscikit-imagein one command - List all installed packages with

pip list

Exercise

Exercise

Organising your code

Structuring your code

- As your code gets more complex, you will want to organise it into multiple files and folders

- This makes it easier to find and reuse code

- Python modules and packages help you do this

- You can also use version control (e.g. Git) to manage changes to your code (covered in the good practices lecture)

Exercise

Exercise

- In a new file

analysis.py, import the functions frommy_funcs.pyand use them - Modularity promotes reuse!

Structuring your code

- As your codebase grows, consider organizing files into directories

Organisation

- Organise your code like you would any other project

- Use meaningful names for files and directories

- Group related functionality together

Documenting your code

Documenting your code

Documenting your code

- Each function should do one thing

- Give functions descriptive names

- This is a form of documentation too!

Comments

Docstrings

- Use docstrings to describe what a function does and how to use it

- Detail inputs and outputs

- Use triple quotes

"""for docstrings

README files

- Single file, usually

README.mdorREADME.txt - Outlines most important information

- What the project does

- How to install

- How to use

- Very useful for others (and future you!)

Next steps

Next steps

- We’ve covered some of the basics

- Next steps – Practice!:

- Mess around with code

- Solve problems

- Google stuff

- Contact

- Additional courses

Further resources

Troubleshooting tips

- Make sure the correct environment is activated

which pythonorwhich pipto check

- Check the scope of your variable

- Pay attention to whether an operation is

in_placeor not- Especially with

pandasandnumpy

- Especially with

- Structure your code as a package as soon as you can

pyproject.toml→ more on this in future sessions!

- Look out for deep vs shallow copies

- Especially with collections (lists, dicts, sets)

Question

Troubleshooting tips

- Read the error messages!

- Google is your friend

- LLMs can help too

- Ask a colleague or contact us

- Use a debugger (e.g.

pdb, or IDE built-in debuggers) - Write tests for your code (e.g. using

pytest)

Comments

#for single-line comments"""for multi-line comments or docstrings